I think we can all admit that dolls are scary.

Even for those of us who don’t start life with pediophobia, movies are sure to give it to us. My own fear of dolls was fostered by such memorable, murderous films as Poltergiest and the Chucky series, and a Twilight Zone episode called “Living Doll.” So when I started to write Spill Zone, my first graphic novel, I knew that a doll would play a part somehow.

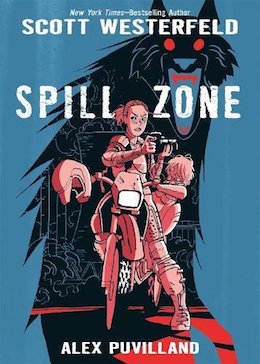

Spill Zone is about a young woman, Addison Merritt, whose hometown and family were destroyed three years ago by a mysterious, unknowable event. Her town is walled off now, full of deadly phenomena, the laws of physics warped inside. Addison sneaks into the Zone to take photographs of the strange apparitions inside, which she sells as outsider art. This is how she supports herself and her little sister, Lexa, who escaped the Spill but hasn’t spoken since the event—except to a doll that she brought out of the Spill, with whom she shares a psychic connection.

Samuel R. Delany once said that science fiction is the genre in which setting is a character. In other words, setting isn’t simply important in SF, it also has some features of personhood. SF settings have backstories, motivations, agendas, and sometimes even a voice. I chose Lexa’s doll, Vespertine, to give my Spill Zone a voice, because I wanted my setting to be the creepiest possible character.

So here’s five creepy things about dolls.

The Uncanny Valley

Too-realistic dolls, like mannequins and Polar Express characters, often fall into the co-called “uncanny valley,” creeping us out by resembling people closely, but then failing to be real upon closer inspection. Evolutionarily, this might be a pathogen resistance strategy, because sick people look a bit glassy-eyed and doll-like, or it may be a cognitive dissonance of an object flitting back and forth across the perceptual categories of human and not-human.

But even rag dolls, like Vespertine or Chucky, can be uncanny, because human beings are social creatures. Our brains are always searching for faces, whether in spilled coffee, castles, or kayaks. And when one of those faces turns out to be a couple of buttons and a squiggle of yarn, it’s weird.

We recognize expressions in the same way as faces, always looking for meaning in a squiggle of lines. The artist for Spill Zone, Alex Puvilland, gave Vespertine one eye that’s a little loose on its thread, so that her expression changes depending on how that eye is dangling. This gave us access to both a full range of emotions and a full measure of creepiness.

Dolls Are Very Old

Humans are interested in humans, a fascination which plays out in all our arts. The oldest cave paintings feature images of people, and many of the oldest sculptures are human figures. A 4000-year-old stone head dug up on the Italian island of Pantelleria, is thought to be part of the world’s oldest toy—a doll.

Of course, there’s no clear line between a dolls that are toys and those that are magic objects, bestowing fertility, good luck, or protection. Or as vessels for sympathetic magic or casting curses.

Now, there’s nothing inherently creepy about something being old or magical. But this ancient need to represent ourselves can be as unsettling as any primal force in human psychology. Looking at toys from history and pre-history always makes me wonder—did those people really see themselves this way? For example…

Dolls Are Made of People

I’m not sure what the earliest instances of dolls with human hair are, but they’ve been around since Victorian times at least. I trust that I don’t have to explain why this is creepy. Bisque dolls hail from the mid-nineteenth century, and have not only human hair but also dead cows in them, because their heads are made of bone porcelain.

Maybe you thought “bone china” referred to the white color, but no. The fanciest porcelain of that era was Josiah Spode’s, which was made of clay mixed with bone ash—cremated bones of cows. So it’s little wonder that there have always been reports of human bones being used to make china dolls. (Holly Black’s Newberry-honor-winning novel Doll Bones plays with the conceit.)

These days, artist Charles Krafft will make you a doll out of your dearly departed’s ashes, doll-reliquaries of your loved ones. Pretty creepy.

Dolls as Racist Caricature

The “Golliwog” first appeared in a children’s book by Florence Kate Upton, published in 1895. With jet-black skin and woolly hair, the character was straight out the minstrel blackface tradition that represented African-Americans as dim-witted and comical.

Though American in origin, the books became hugely popular in England, especially after the Golliwog was adapted as the mascot of the James Robertson & Sons jam company. Dolls based on the character were one of the most popular toys in Europe across the twenty-first century, spreading American blackface iconography, with all its attendant meanings, throughout Europe. And the term “golliwog” became part of the lexicon of racial slurs. (James Robertson didn’t remove the final vestiges of the character from its marketing until 2001.)

Racist caricatures will always be a problem with dolls. We humans assume that a doll with no racialized features—a simple ball of clay with two eyes, say—must represent the dominant ethnic type, just as a character in prose who has no racial descriptors is assumed to be white. So when the doll-maker starts to add features which represent race, a minefield of negative representations always awaits.

Dolls can be tricky as shit, and yet…

Kids Like Them

This is perhaps the creepiest thing about dolls—kids want them in their arms, in their rooms, in their beds. To us adults with better developed pediophobia, this can seem weird and even menacing.

Kids use dolls to model relationships while they play. Dolls get sick, have fights, care for each other, converse, have tea—all the things that kids see their adult and fictional models doing from day to day. They are imaginary friends (and imaginary children, parents, siblings), which is of course healthy and normal. But imaginary friends signal something different to us adults. They are the voices in our heads, the fears in our subconscious, the dolls in our closets.

One of my favorite affordances of comics is that we get to read thoughts without hokey voiceovers or clumsy italics. In Spill Zone, we can “hear” Lexa’s and Vespertine’s conversations without intruding into the rest of the story. And I can make the reader wonder whether this rag doll is really just an imaginary friends or some kind of entity that hitched a ride out of the Zone.

Which parallels the question that every adult really should ask themselves when they see a kid talking to a doll—is that conversation really all generated by the child? Or is it also imbued with thousands of years of primal doll magic, all the wonder and evil of human culture and history and care and violence given voice?

What do the kids know that we’ve forgotten?

Top image: “Living Doll”, The Twilight Zone (1963)

Scott Westerfeld is the author of the worldwide bestselling Uglies series and the Locus Award–winning Leviathan series, and is co-author of the Zeroes trilogy. His other novels include the New York Times bestseller Afterworlds, The Last Days, Peeps, So Yesterday, and the Midnighters trilogy. Spill Zone, illustrated by Alex Puvilland, is available now from First Second.

Scott Westerfeld is the author of the worldwide bestselling Uglies series and the Locus Award–winning Leviathan series, and is co-author of the Zeroes trilogy. His other novels include the New York Times bestseller Afterworlds, The Last Days, Peeps, So Yesterday, and the Midnighters trilogy. Spill Zone, illustrated by Alex Puvilland, is available now from First Second.